Let me tell you a little story. There was once a child so young, they couldn’t understand causality, morality, or social responsibility. The teachers and nurturers in this child’s life needed to impart some basic life lessons and help train skills early, but the child didn’t have the attention span to follow long, elaborate explanations. So what did they do? They communicated those lessons in a story…

Children’s stories are a means of entertainment, sure, but they’re so much more than that. The tradition of telling stories to kids dates back as far as civilization itself, and seems to have arisen independently in cultures across the globe. This suggests that children’s stories are more than just a way to keep kids quiet for a few minutes.

When you look at these stories as a whole — from classic children’s stories told around campfires to kids reading online some millenia later — you see distinct trends and themes emerge, regardless of geography, language barriers, or time. Moreover, you see the artform develop and evolve alongside civilization, taking advantage of new technologies to further old goals.

In this article, we take a look at that evolution. We chart the progression of children’s stories from their oral origins in prehistoric times all the way up to kids books online. When looking at their role in raising a child, we see that these stories are often more than just stories...

Oral Tradition Around The World

The history of story-telling, whether for children or adults, always begins with oral tradition. Before humans could read and write, we could only talk and listen. Our shared heritage stems from shared meals over a campfire, and even cavemen enjoyed a little conversation while they ate.

Oral tradition refers to the stories passed down from generation to generation: fables, folklore, fairy tales, proverbs, and (as we explain in the next section), myths. While oral tradition undoubtedly played a significant role in the societal development, before and after the written word, unfortunately it’s nearly impossible to track. All we have are the written records of oral tradition, which are paradoxically not “oral.”

So we glean what we can about the spoken stories from their written counterparts. There are some considerations in mind, though. For starters, we know the stories that were actually written down must be the cream of the crop, considering the effort involved in writing in the early years. We can only guess at what the unpopular stories were like.

We also know that each speaker of the story added their own creative twists and styles, allowing for discrepancies in the same story from neighboring groups of people. This is significant for two reasons:

- The stories we know about today are often only the version of the written author; whatever competing variations that were not written down are lost.

- Stories demonstrate cultural identities, so in some cases major elements were changed to cater to the audience.

Rather than focusing on the differences, we prefer to look at the similarities. Diving into the content of the stories, we see identical themes emerge from sources on different ends of the Earth. This proves that certain styles of storytelling were more effective than others, and also that different societies have similar goals, i.e., raising intelligent and thoughtful children.

Of the common themes, we’ve listed the three most prevalent — no doubt you’ll recognize some from your own childhood…

Anthropomorphism

“Anthropomorphism” is just a fancy word for “things acting like humans,” typically animals. Attributing human characteristics to animals — speech, rational thinking, intelligence, emotions — has always struck a chord with children.

Even today, in kids books online or off, there’s plenty of animal main characters. Just look at one of 2019’s best-selling story books for kids, The Way Home for Wolf. This is the latest in a long tradition including the likes of Stuart Little, Splat the Cat, Frances the Badger, and the cast of Charlotte’s Web (not to mention their film and TV peers from the Looney Tunes and Disney).

The anthropomorphism in the popular children’s stories today have deep roots in oral tradition. The twentieth-century The Berenstain Bears seem faintly related to the nineteenth-century “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” — which itself is a retelling of an even older version in which the Goldilocks character is an old woman and the bear family is just three adult bears, albeit differently sized ones.

Source: Illustration by Arthur Rackham (1918), via Wikicommons.

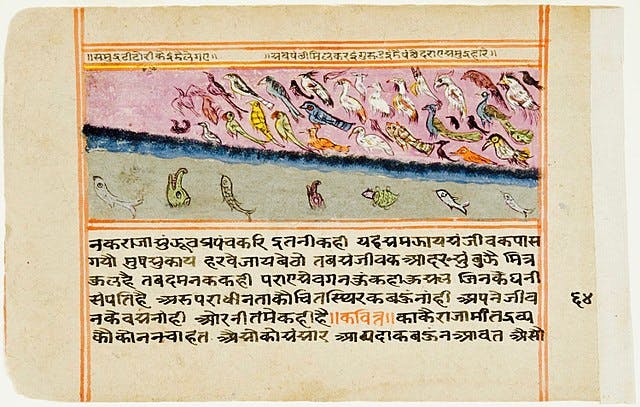

But the concept of animals doing human things like eating porridge didn’t start there. Some of humanity’s oldest works feature anthropomorphized characters, including Aesop’s Fables (~500 B.C.E.), a collection of ancient Greek oral tradition and the source of some of the West’s most popular children’s stories, such as “The Ant and the Grasshopper.” Similarly, ancient India’s The Panchatantra (~200 B.C.E.) features a collection of animal fables recorded from older oral stories.

Source: Panchatantra manuscript page from 18th century, via Wikicommons.

Interestingly, certain animals tend to have similar personality traits, based in reality. For example, different tribes of indigenous North Americans all depicted the playful coyote as a clever trickster, even when they didn’t have contact with one another.

Morality

Since the beginning, one of the most prevalent methods for imparting morals on a new generation is through story-telling. Look at one of the most popular children’s stories of all time: “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” one of the aforementioned Aesop’s Fables. Rather than tell a child that lying is wrong, the fable shows them the consequences through the story — if you lie, people stop trusting you.

Of course, the trouble comes when a culture’s values change over time. The history of children’s stories is filled with tales whose morals have become outdated or otherwise inapplicable.

A prime example of a fairy tale that didn’t age well is “Bluebeard,” a man who continually murders his wives. Although his final wife ends his tyranny and avenges the previous wives, the moral often amounts to “curiosity is dangerous” or even “don’t second-guess your husband” — placing the blame on the innocent wife instead of the monstrous murderer.

Explaining Natural Phenomenon

Keeping in mind that oral tradition started thousands of years before the scientific process, you can understand how children stories could be used to explain the natural world… even if incorrectly.

This is often combined with anthropomorphism to show how animals became the way they are. A good example is the Namibian story of how zebras got their stripes — spoiler alert: a zebra and a baboon fight over water, leaving the zebra with burn-marks and the baboon with a red butt.

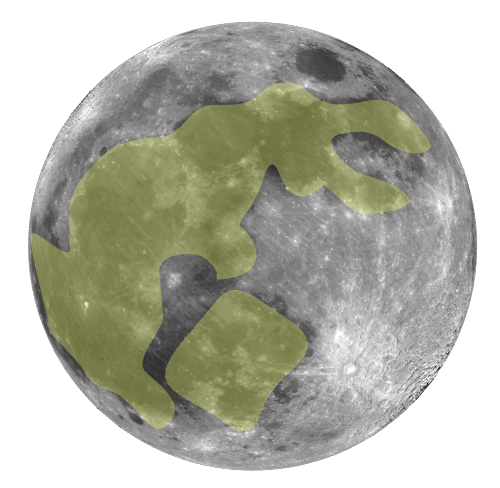

Another popular example is the moon rabbit folklore popular in East Asia. The story suggests the designs on the moon look like a rabbit using a mortar and pestle, something akin to the “face” of the moon in the West.

Source: Wikicommons

The details of the story change from region to region, with distinctly different versions emerging in China, Korea, and Japan. However, the key details are the same: it’s always a rabbit with a mortar and pestle, because that’s what the shape on the moon looks like.

Although early stories explaining the natural world lack educational value, they tend to be more entertaining. We’re also tempted to think these stories came about from frustrated parents hoping to placate a child with unanswerable questions.

* * *

As civilization developed, in recent millennia, story-telling methods grew more sophisticated and become implemented in more aspects of society. One of the most noteworthy — especially when discussing stories for kids — is the connection to religion and mythology. Early pantheistic religions used stories for kids to establish a definitive moral code and explain natural phenomena.

Children’s Stories and Mythology

All the popular pantheons of the ancient world passed on their belief systems and values through myths — which are just another type of story, often for children. Mythology in general isn’t exactly targeted to children, but certain myths are. When we examine the stories for kids, we can see how they evolved from the structure of earlier oral traditions.

The Bigger Story

The main difference between myths and independent stories is that myths fit into a greater framework. Whereas the oral stories for kids tend to be standalone tales, myths are all part of greater “universe,” with recurring characters and ongoing themes. And because religion is so closely linked to culture, the myths themselves became a source of cultural identity.

Look at the Greek myth of Arachne, in which the goddess Athena punishes a young weaver for her arrogance by turning her into a spider. As a standalone story, this is a good example of imparting a moral lesson to children: don’t be conceited.

Source: Minerva and Arachne, René-Antoine Houasse (1706), via Wikicommons.

But in the greater context of Greek mythology, we see a lot of other elements at play. For one thing, characters being punished by the gods is quite common in Greek mythology. Any regular listener of Greek myths would have no trouble guessing the ending.

You also have a consistent representation of Athena, goddess of wisdom. In most versions of the myth, Athena scorns Arachne for her pride; but in some accounts, she does it as a reward so that Arachne can continue weaving forever. What’s interesting is that the antagonist in a story about pride is the wisest goddess, hinting that arrogance is an absence of wisdom.

Creation Myths

Also on-brand for religions is explaining how the earth came to be through creation myths, an extension of explaining natural phenomenon. These myths, too, are skewed to the beliefs of the coinciding religion.

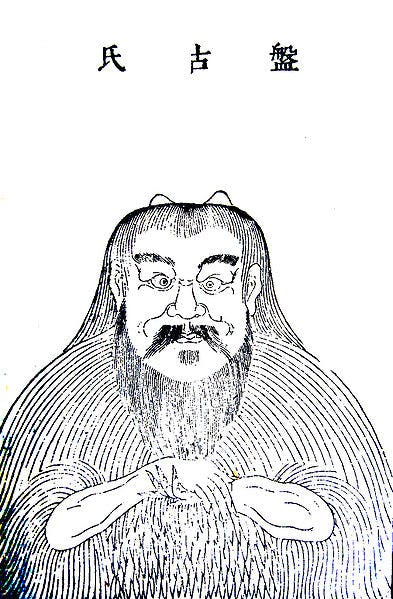

For example, the Chinese creation myth of Pangu explains the origins of not just the universe, but also of the concepts of Yin and Yang, which play a large part in Chinese philosophy. The story itself could be told without mentioning Yin and Yang; however, their inclusion unites the myth to the bigger patchwork of the Chinese cultural identity.

Source: Pangu from Sancai Tuhui (~1607), via Wikicommons.

Similarly, Egyptian mythology makes frequent references to the concept of Ma’at, the ideology of order, truth, and justice, and the goddess who represented these ideals. Many Egyptian myths for children discuss the struggle between Ma’at and her opposite, Isfet, representing chaos, violence, and evil.

By giving the abstract concepts of “order” and “chaos” a human-like personification, it makes them easier to explain to children. Through the lens of a fairy tale, the Egyptians found a way to discuss complicated ideas like civilized society, entropy, and legal systems so that even a child could understand.

* * *

Though oral tradition and mythology make up the majority of storytelling in human history, historians tend to focus on the written texts simply because it’s all they have! As mythology fades away from civilization, we start seeing more advanced literary techniques as oral tradition gives way to good, old-fashioned writing.

A Light in the Dark Ages

In Western history, the Medieval era is known as the “Dark Ages” because scientific and political progress seemed to stagnate. But for other parts of the world, this time seemed bright...

A Golden Age for Chinese Literature

An “early adopter,” China started using a basic form of woodblock printing in 593 A.C.E. This technology, in conjunction with other factors, helped instigate the cultural golden age of the Tang Dynasty, which ruled from 618 to 907 A.C.E.

Alongside the great advancements made to Chinese literature and drama, the Tang Dynasty also saw an insurgence in children’s poetry. These poems served virtually the same goals of other stories for kids — imparting life lessons in a way that “even a child could understand.” Look at how the poem “Toiling Farmers” helps build a healthy attitude towards gratitude:

Farmers weeding at noon,

Sweat down the field soon.

Who knows food on a tray

Thanks to their toiling day?

Comparable to Western children’s songs like “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” or “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” these Chinese kids poems were often memorized and practiced over and over. They, too, adhered to many of the pillars of oral tradition, including plenty of animal characters.

The advent of printing didn’t slow down oral tradition, either. A few centuries later, the Song Dynasty (960–1276 A.C.E.) saw a spike in popularity for professional storytellers. Ranging from stand-up comedians to historians, these professional entertainers were paid to perform at fairs, festivals, teahouses, wineshops, and sometimes personal residences.

Combined with their musical performances, these storytellers were not unlike the children entertainers of today. One important aspect of these storytellers was community-building and bringing people together, as almost all of these performances were public where children and adults from the neighborhood would gather together to listen.

The Significance of 1,001 Nights

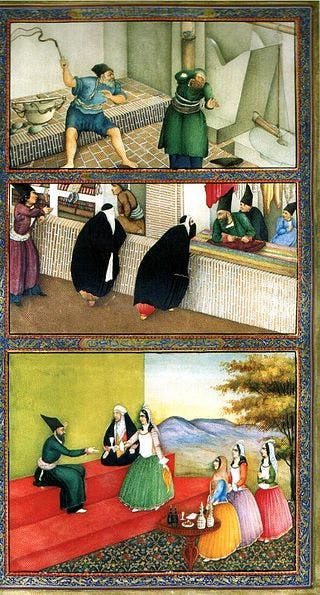

The Middle East is another culture to see a golden age in the Medieval Era. During the Abbasid Caliphate of 750–1258 A.C.E., the religion of Islam had hits its stride, unifying the Middle Eastern people and reinvigorating their culture. Arts and literature flourished during this period, not the least of which was the legendary book 1,001 Nights, a.k.a. 1,001 Arabian Nights.

Source: Illustration of 1,001 Nights by Sani ol Molk (1853), via Wikicommons.

Although not explicitly written for children, with some sexual and violent references, the book nonetheless appealed to children thanks to its fantasy elements — it reads like a fairy tale, with magic, monsters, and mermaids. Add to that a strong emphasis on morals and lessons for each story, and you have all the makings of a classic children’s book.

The book itself is more of a collection of short stories, all united under one greater frame story where the storyteller Scheherazade tells these tales to her husband, the king Shahryar, to delay her execution by entertaining him. The stories are thought to be traditional folklore from Persia and the Middle East, with some stories suspected to come from India as well.

1,001 Nights is significant not just in children’s literature, but in all literature. Considering when it was written, this book provides some of the earliest examples of popular literary techniques still used today:

- Frame story — A story within a story, where a character narrates a secondary, independent tale.

- Accompanying illustrations — 1,001 Nights is one of the very first kids stories with pictures (in subsequent editions; the original is text-only).

- Repetition — Literary repetition is a common technique where you highlight certain words, phrases, or themes by repeating them at different parts in the story.

Along with its contributions to literature, 1,001 Nights also introduced the world to some beloved elements of Middle Easten folklore, such as the magic carpet, genie (djinni), and Rocs (deadly giant birds). Ironically, the book is not as cherished in the modern Middle East as outside it.

* * *

As civilization matured, so too did religion. If mythology was a step up from oral tradition, then the religious texts of the Medieval and Renaissance eras were a step up from myths. The stories themselves become more eloquent and begin to form narrative trends, but at the same time they were pulled towards specific morals more than ever — for better or worse.

The How-to Guides of the Renaissance

It’s not fair to say that Europe in the Dark Ages was devoid of all children’s stories. Oral tradition continued to entertain kids with regional myths and folklore, while original works like the tales of Camelot or early Druidic fairy tales added something new.

But it isn’t until the Renaissance of the 1500s that history again sees progression in story books for kids. By then, the Gutenberg printing press (1450) had been widely integrated into Western society, paving the way for more experimentation in book-writing. As with other aspects of European culture, this era rejuvenated the art of raising children through stories, though almost always with a religious slant.

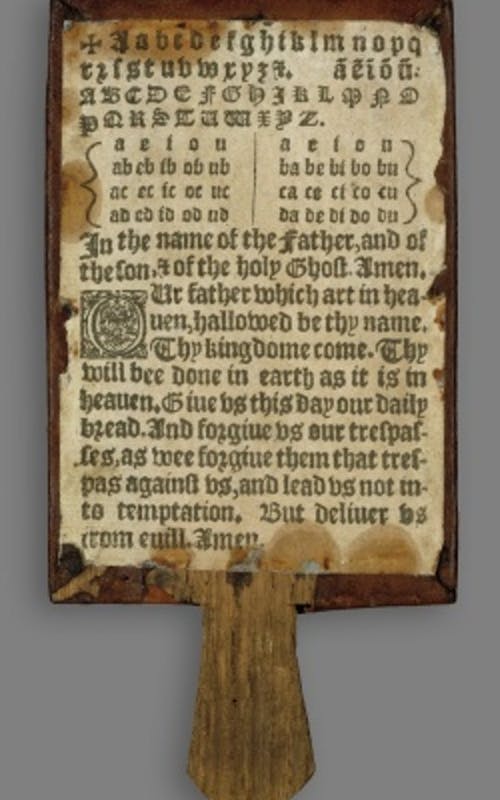

Hornbooks

Despite the image the name conjures up, hornbooks were actually something like paddles with educational texts written on them — usually the alphabet, but religious texts or prayers were also common. With the earliest usage recorded at 1450, hornbooks were a main resource in children’s education throughout the 1500s and 1600s, in both England and colonial America.

Source: The Conversation.

Hornbooks get their name from a thin, transparent sheet of horn (or mica) stretched over the writing to protect it. The wooden handles were used to hang it from the child’s girdle for easy transportation (and to reassure parents that they wouldn’t lose it).

Etiquette Guides and Religious Catechisms for Kids

While hornbooks taught fundamental education and basic religious values, more serious texts were dedicated to children’s etiquette. This tradition actually started in the Medieval era, with a few children’s poems written into the Codex Ashmole 61 to explain common courtesy, not unlike the more prevalent Chinese counterparts.

However, it wasn’t until the 1530s that the English language had a formal children’s book for etiquette. Written by Desiderius Erasmus in Latin and later translated to English, On Civility in Children, a.k.a., A Little Book of Good Manners for Children, offered classic and timeless advice for kids, like:

To fidget around in your seat, and to settle first on one buttock and then the next, gives the impression that you are repeatedly farting, or trying to fart. So make sure your body remains upright and evenly balanced.

Later etiquette books abandoned their pretense and evolved into straight-up religious catechisms for children. In fact, the very first children’s book published in the (colonial) United States was such a text: Spiritual Milk for Boston Babes. Written by the minister John Cotton in 1656, this behavioral guide was structured like a 15-page FAQ pamphlet, with 64 questions and answers about the Puritan faith.

Another Puritan text for children, A Token for Children, seems quite bleak by modern standards. The 1671 book, written by James Janesway, accounts the deaths of 13 children to show what it takes to get to heaven. This excerpt shows the tone you might expect:

How art thou affected, poor Child, in the Reading of this Book? Have you shed ever a tear since you begun reading? Have you been by your self upon you knees; and begging that God would make you like these blessed Children? Or are you as you use to be, as careless & foolish and disobedient and wicked as ever?

Judging by these books, it appears children’s stories during this era had forgotten the importance of entertainment in educating children — something that was readily addressed over the next century.

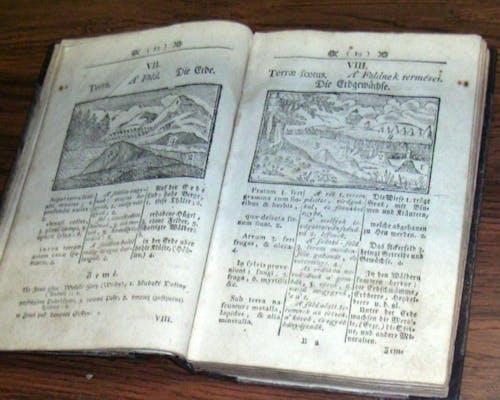

The First Kid’s Stories with Pictures

While books with illustrations were not uncommon, the picture book as we know it, with drawings on each page, didn’t come about until 1658. The Orbis Pictus, written by Czech philosopher John Amon Comenius, was a monumental success throughout all of Europe.

Orbis Pictus. Source: Wikicommons.

Although the source text was written in Latin, it often included accompanying translations in the child’s native language to improve kids’ reading comprehension. Specifically, the text covered natural themes like zoology and botany, as well as conventional religious discussions.

* * *

Though their hearts seemed to be in the right place, a lot of stories for kids in the Renaissance fell short. Looking back, it seems even the simplistic oral folklore had more heart. We can thank the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke for transitioning the history of children’s stories into what we recognize today.

The Enlightenment Lives Up to Its Name

If you took offense to how religious texts spoke to children, you’re not alone — many people who lived through the Enlightenment felt the same way. During this period, we see children’s literature shift into a form we recognize today, largely in response to the “Father of Liberalism” John Locke.

Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education

In 1693, John Locke published a small book, Some Thoughts Concerning Education. Although not a children’s book itself, Locke’s text single-handedly revolutionized stories for kids by logically building the argument for better education. At the time, children’s education was largely translating texts from Ancient Greece and Rome, whereas Locke advocated more direct study of modern science, mathematics, and contemporary languages.

In the groundbreaking essay, there was another idea that rang true for most people: learning should be fun. In addition to ideas about using dice games to teach children, Locke’s treatise also suggested “easy, pleasant” books, kid’s stories with pictures, and children’s books with actual stories for teaching kids reading.

Locke’s theories were not ignored, and jump-started a pivotal shift in how we approached stories for kids.

The Origin of Classic Children’s Stories

Across the English channel, the French writer Charles Perrault was already testing Locke’s theories on using entertainment to teach kids reading comprehension. His 1697 collection Tales and Stories of the Past with Morals; Tales of Mother Goose gathered the classic children’s stories from years of oral tradition and popularized the “fairy tale.”

While you may not have heard of Perrault or this book before, you’ve almost certainly heard its tales. Included in this kid’s book are some of the most popular children’s stories ever told, including Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, and the original Cinderella.

Source: Sleeping Beauty, by Henry Meynell Rheam (1899), via Wikicommons.

The success of Perrault’s works coincided with both the beginning of Enlightenment ideals and the popularity of literary salons in France. Aside from providing a cornerstone of children’s literature that lasted into our modern era, the book also helped inspire other children’s authors to follow, including John Newbery, the so-called “Father of Children’s Literature.”

The Father of Children’s Literature

Locke’s ideas lead people to rethink how they approached story books for kids. Throughout the 1700s, people embraced the idea that children can and should enjoy learning, leading to a new market for children’s stories.

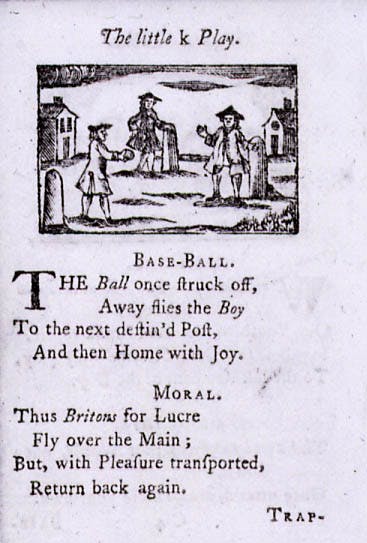

The theories of Locke struck a chord with one English writer John Newbery, later dubbed “The Father of Children’s Literature.” One of his earliest successes was a short children’s book with a long title: A Little Pretty Pocket-Book Intended for Instruction and Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly. Published around 1744, this book reflected the economic upturn of the time period with brightly colored paper and accompanying toys sold with the book.

Source: Excerpt from Little Pretty Pocket-Book… showing an early depiction of baseball (~1760), via Wikicommons.

This success launched Newbery’s career in children’s books and proved to the world that stories for kids could be profitable. He continued pushing the envelope for children’s literature, and in 1751 he published the first periodical for children, The Lilliputian Magazine.

However, his most famous work is generally considered to be The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes (1765). Said to be the first children’s novel, it tells a story vaguely reminiscent of Cinderella, though without the magic or glass slippers. Harkening back to the thread of morality woven into the history of children’s literature, this story shows how an honest and hard-working woman earns her happily ever after.

The modern-day Newbery Medal, awarded to distinguished and popular children’s stories, was named in his honor.

* * *

Once it had been proven that children’s stories were successful at both teaching kids reading and making money, the floodgates opened wide. Add to that the financial successes of Victorian England, and it’s easy to see that the golden age of children’s literature was just beginning.

Victorian Era: The Golden Age of Children’s Literature

When we think of children’s literature, we often think of some tentpole books: Alice in Wonderland, Tom Sawyer, Pinnocchio, and works of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Anderson. It’s no coincidence these were all written during the same era, and it’s no surprise this era is dubbed the “golden age” for children’s stories.

The Popularization of Fairy Tales

On the heels of Newbery’s success, writers were looking for ways to break into writing for children. Some found inspiration in the old model of Charles Perrault — collect classic folklore and repurpose it as short stories for kids. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

That’s the model that led to the success of both the Brothers Grimm in 1812 and Hans Christian Anderson in 1835.

Like the children’s stories in Perrault’s collections, the works of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Anderson are known by heart to most Westerners from their childhoods — and indeed the rest of the world is becoming familiar with them as well.

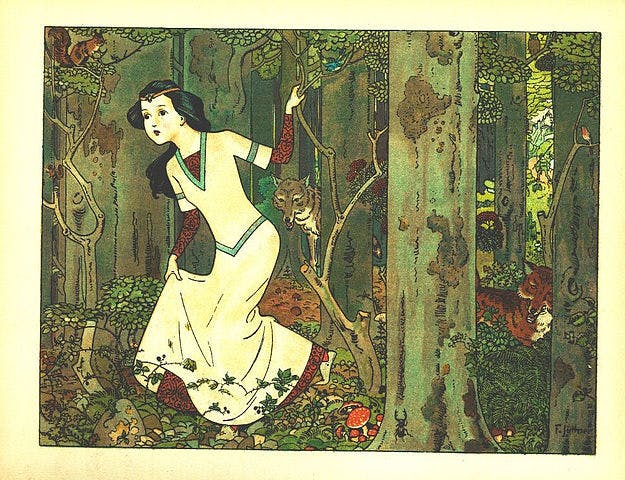

Spread across two volumes, the German Grimms’ Fairy Tales contain the well-known tales of “Snow White,” “Rapunzel,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Hansel & Greteal,” and retellings of “Cinderella” and “Sleeping Beauty.”

Source: Snow White, or Schneewittchen in German, by Franz Jüttner (1910), via Wikicommons.

Despite their success, the stories were criticized, then and now, for their dark and mature themes (like kids murdering a cannibal witch by locking her inside an oven). This led to constant tempering and censoring of the tales through later editions — the most noteworthy of which is changing the biological mother into the now-archetypal “evil stepmother.”

Similarly, the Danish author Hans Christian Anderson also collected fairy tales for children into his books, although during his lifetime his success came from his adult writing. Anderson is responsible for recording classic children's stories like "The Little Mermaid," "The Snow Queen," "The Princess and the Pea," "The Ugly Duckling," and "The Emperor's New Clothes,"

Hans Christian Anderson is now known exclusively for his children’s stories, and has inspired other noted children’s authors like Beatrix Potter (The Tale of Peter Rabbit), A. A. Milne (Winnie the Pooh), and even Lewis Carroll, who later changed the trajectory of children’s literature forever.

Novels for Children

While Newbery proved that children’s stories can effectively fit the structure of novels, a century later Lewis Carroll showed that they can also display deeper literary themes as well. In Alice in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871), Carroll experiments with more adult literary techniques to usher in the next stage in the evolution of children’s stories.

Source: Original illustrations by John Tenniel (1865) for Alice in Wonderland, via Wikicommons.

Carroll’s works rely on symbolism more than any other children’s stories prior, except for maybe the more direct fables and proverbs from the oral tradition era. Carroll starts a trend of speaking to children like adults, and many adults were surprised to see that it worked.

Subsequently, we saw a rise in children’s books with a more sophisticated and mature tone. Little Women (1868), a literary milestone, was actually pitched to Louisa May Alcott by her publisher who wanted to capitalize on the children’s book trend. Ironically, Alcott was originally against the idea.

Likewise, the American classics The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) both dealt with adult themes and complicated life lessons, though disguised as children’s books. Aside from discussing race relations in the newly liberated south, Mark Twain’s books also show intricate character development uncommon to stories for kids at that time.

Despite the maturation of children’s literature, the traditional elements — like anthropomorphism — remained just as popular among young readers. This is evidenced in the legacies of classics like Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty (1877) and Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894).

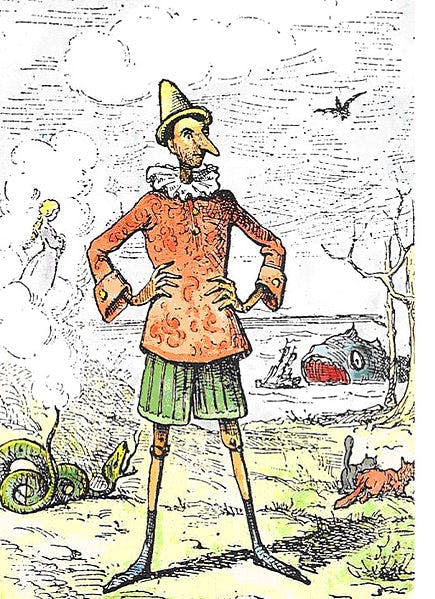

Other novels for children to arise in the wake of Lewis Carroll’s success include The Princess and the Goblin (1872), a lesser-known high fantasy predecessor that’s said to have inspired Tolkien. Another example is the Italian classic The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883), by Carlo Collodi, which draws on the strong tradition of morality in children’s stories to create one of the strongest metaphors for lying, the long nose. (Interestingly, modern science has proven this somewhat true — lying causes an increase in blood flow to the nose, sometimes causing it to swell.)

Source: Original artwork for Le Avventure di Pinocchio (1883) illustrated by Enrico Mazzanti, via Wikicommons.

The Victorian era also sees the birth of the science fiction genre with influential authors H. G. Wells of England and Jules Verne of France. Although not exclusively for children, their works of fantasy adventures captured the imaginations of children everywhere. Novels like Wells’s The Time Machine (1895), steeped in symbolism and social commentary, pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable for children.

The works of Verne in particular — Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873) — have since been adapted into children’s films and are now considered classic children’s stories.

* * *

Thanks to Victorian ideals, children’s literature became actual literature, sharing the writing techniques and quality standards of adult books. This naturally led to the modern-era of story books for kids, and our current place in the evolution of children’s stories

Twentieth Century: Children Stories as We Know Them

The Victorian Era is known for its accomplishments in literature — for both adults and kids — and changed book writing forever. With stories for kids, the greatest change was the more mature subject matter; based on the successes of the 1800s, children’s authors saw they no longer needed to “sugar-coat” their stories and could deal with more adult themes.

However, this didn’t happen overnight. The early half of the twentieth century saw more of a transition into the “adult” children’s stories, with one foot on each side.

The Turn at the Turn of the Century

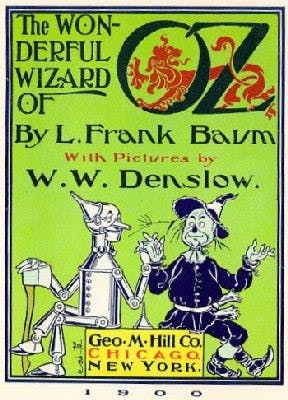

The first few decades of the 1900s continued the legacy of Victorian era children’s stories. Right off the bat in the year 1900, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by the American L. Frank Baum kicked off the new century of stories for kids. With the Library of Congress calling his work “America's greatest and best-loved homegrown fairy tale,” Baum himself cited the inspiration of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Anderson.

Source: Wikicommons.

Not to be undone, Britain attempted to regain its prominence at the forefront of children’s literature. Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie created Peter Pan as a minor character in his book The Little White Bird (1902), only later giving him the spotlight in the play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up (1904). Following the play’s success, Barrie adapted Peter’s adventure into the novel Peter and Wendy (1911), which fits the story we know today.

That same year, Frances Hodgson Burnett published another classic kid’s book, The Secret Garden. Somewhat of a sleeper hit, the book didn’t receive much recognition until decades later; it wasn’t even mentioned in Burnett’s obituary when she passed in 1924.

Although not as famous as other fantasy series, the Brazilian epic series The Yellow Woodpecker Farm published the first of its 23 books in 1920. Written by Monteiro Lobato, the series is regarded on the same level of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz or the later Narnia Chronicles. The plot revolves around two children who go on magical adventures with their anthropomorphic toys, including the series’ favorite, a free-thinking (and sometimes anarchistic) living rag doll named Emília.

But perhaps one of the most indicative children’s stories of this period is the start of the Mary Poppins series by the Australian-British P. L. Travers. The first of eight books was published in 1934, and demonstrated elements of magic realism, where otherwise realistic settings are disrupted with fantasy elements; i.e., a flying nanny. This starts off a theme carried over by many other stories for kids, and continues to this day.

Post-War Postmodernism

The aftermath of the world wars brought about the postmodern era, rife with irony, cynicism, and moral subjectivism. Although stories for kids were often immune to these grittier elements, we still see them seep through.

One of the more subtle examples is Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline series, a story about Paris, written in English by an Austrian-American. Although there’s nothing controversial about this series, it does start to deviate from the standard conventions and morality of the time, in true postmodern fashion.

Similarly, Sweden’s Pippi Longstocking, by Astrid Lindgren, also features an assertive young girl as the protagonist, one who is at times blatantly disrespectful of adults. This is a distinct departure from the well-behaved, model children that populated most of the children’s stories throughout history.

To really see the impact of free-spirited characters of Madeline and Pippi, compare them to their contrasting contemporaries in the Dick and Jane primers, which showcased the more “vanilla” ideal of polite children in the 1950s, including a dog named “Spot.”

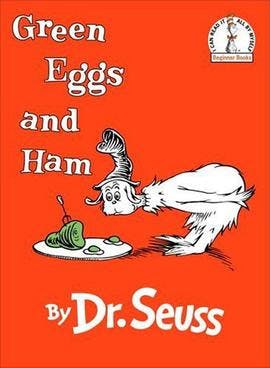

Moving forward, the works of Dr. Seuss are more noticeably unorthodox. Throughout the 1950s, the works of Dr. Seuss waded into absurdism, with nonsense words and obscure rhyme schemes. But since children couldn’t put them down, the parents didn’t mind.

Source: Wikicommons.

This postmodern era also saw the emergence of the fantasy epic — or reemergence, if you consider the antiquity epics like Gilgamesh or the Odyssey. The 1950s saw the publication of both J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia. These paved the way for more progressive structure in children’s book, which modern authors made excellent use of.

Modern Era - More Mature than Ever

The long history of children’s stories sees it progress more and more to adult themes; it seems each generation of children is capable of handling more sophisticated writing, or maybe each generation of parents is more comfortable sharing mature themes with their young.

One of the earliest pioneers of this new style was Roald Dahl, who reconnected children’s stories to their dark and violent past. Dahl’s novels for kids like Matilda (1988) and James and the Giant Peach (1961) don’t shy away from mature themes like child abuse, while Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) sees the same deadly punishments for children as literature from the Medieval and Renaissance eras.

Although not as macabre as Dahl, progressive author Judy Blume also sought to challenge what’s appropriate for children. Her novels, including Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret (1970) and Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing (1972), dealt with issues children faced in the real world, including masturbation, menstruation, birth control, and death.

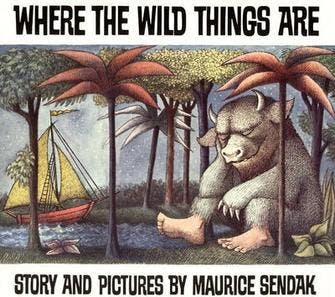

These more mature and realistic books, including a number of Blume’s works, were often banned when they were first released. Even Maurice Sendak’s now-classic Where the Wild Things Are (1963) was banned for its first two years, partly because its depiction of anger and children’s temper tantrums.

Source: Wikicommons.

But the more time that passed, the open-minded society became about what could go into stories for kids. Just look at Neil Gaiman’s Coraline (2003), which goes beyond “adult” themes into outright horror, to the amusement of young readers and literary critics alike.

This ultimately opened the doors for our modern classics, including J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series (1997-2007) and its early contemporary, Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials (1995-2000). Both series continue the tradition of the fantasy epic, as did the later Hunger Games series (2008-2010) by Suzanne Collins.

The Future of Children’s Literature

So where do we go from here?

In the 2000s, we’re seeing more of a social awareness to diversity and inclusiveness, which has largely been absent from the Western writings of the last few hundred years. We’re seeing a lot more main characters of color, religious diversity, and depictions of alternative lifestyles like same- sex parents. To a lot of people’s surprise, the children readers don’t mind this one bit!

In the past twenty years, technology, amongst other things, is also allowing new and unique experiments in children’s stories. Personalized children’s books seem to fit the values of modern literature like a glove, with books using actual photos, and sometimes avatars, of the reader in the illustrations. If the goal of children’s books is to encourage them to read more, placing them as an actual character is a great way to keep them interested!